A new report from the Prison Policy Initiative explores the ways the criminal justice and child welfare systems can punish families and worsen the conditions that got them ensnared in those systems in the first place.

The report encourages policymakers and reformers to broaden their views of the criminal justice system beyond jails, prisons, parole and probation. It highlights how the justice system is intertwined with the child welfare system — and the ways both can punish parents, particularly poor people and people of color.

“In the absence of flourishing social safety nets, both the criminal legal and child welfare systems have become catch-all nets to address social issues that they’re not equipped to deal with,” writes Emma Payton Williams, a researcher with the Prison Policy Initiative, noting that both systems respond to mental health crises and substance abuse issues with forced treatment and punishment.

“Criminal legal system and social work advocates must ask, can we address issues in the criminal legal system by investing in another system that’s riddled with the same problems?” Payton Williams asked.

Here are some other key takeaways from the report:

- More than half of people in prisons nationwide are parents — compared to about one-third of people in North Carolina’s prisons. The Prison Policy Initiative report points to research to argue there’s a link between involvement in the justice system and the child welfare system. A study from 2017 found that 40% of children in foster care had a parent imprisoned over the course of their lifetime.

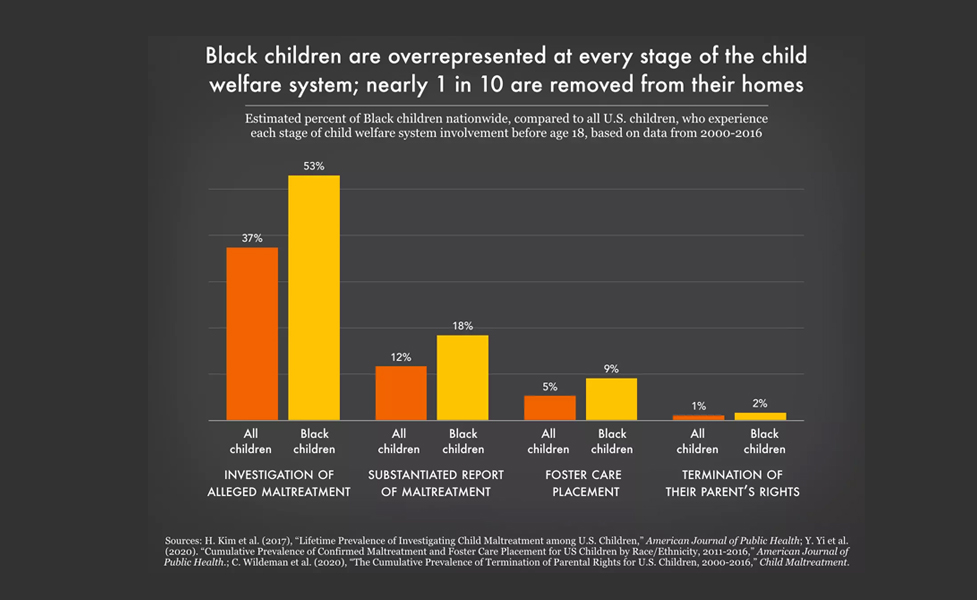

- Black and brown families are consistently overrepresented at every stage of the child welfare system. Black and Indigenous parents are more likely to be reported to and investigated by child protective agencies, and those parents are more likely to have their parental rights terminated. In a presentation in North Carolina last year, a senior policy fellow at the University of Chicago said that half of all Black children experienced a Child Protective Services investigation, calling it “a normative experience in the lives of Black children.”

- Those in prison are more likely to have been in foster care, and children in the foster care system are more likely to wind up imprisoned.

- Most of the time, families come into contact with the child welfare system because of allegations of neglect, not abuse. There were nearly 4 million calls made to child protection agencies in 2021, over three-quarters of which involved claims of neglect. About half of those calls were quickly screened out, deemed to be illegitimate allegations or to lack enough information to meet the criteria for a report.

- One potential solution: Give struggling families money. Neglect claims often involve parents who do not have the resources to care for their children; giving them cash, advocates argue, allows them to get through periods of financial hardship and keep their families together.

- A related potential solution: give money to formerly incarcerated people. Durham launched a guaranteed income pilot program for formerly incarcerated residents in 2022, giving 109 people $600 a month for a year. “I’ve gotten all kinds of emails and texts of folks saying you’re giving money away to ex-cons,” Mayor Pro Tem Mark-Anthony Middleton told ABC 11 last year. “Surprise, surprise folks paid bills and did things for their kids.”

Click here to read the Prison Policy Initiative’s report, titled “Force multipliers: How the criminal legal and child welfare systems cooperate to punish families.“