By DR. JOYNICOLE MARTINEZ, Staff Writer

In the last 20 years, Ukraine has emerged as a choice destination for African and other international students due to the high-quality education offered and relatively low tuition and fees. Ukraine was home to over 76,000 foreign students, according to government data from 2020. Nearly a quarter of the students were from Africa, with the largest numbers coming from Nigeria, Morocco and Egypt.

Ayoub, a 25-year-old Moroccan pharmacy student, had built a life he was proud of in Kharkiv, a city in the country’s northeast. He was due to graduate in three months, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has forced him to flee the country, and with the invasion came an exposure to danger and a level of racism he had not previously experienced. With a group of students, Ayoub arrived in Lviv, 50 miles from the Polish border hoping to make it to safety. He did not expect to be stopped.

“They wanted Ukrainians to go first, so it was white people who got priority. Taxi drivers were also charging us crazy money, but I thought there will always be opportunists, even in war. It wasn’t until I reached one of the ‘checkpoints’ on the approach to the Polish border that I was actually pushed back and told to wait,” Ayoub explained.

Instead of waiting, he chose to try crossing into Hungary, but found the racism met him there. “When I spoke to the guards in Russian, they told me I should be speaking Ukrainian and questioned whose side I was on. That was really upsetting because I had worked so hard to learn Russian, not just speak it, but read and write it as well.”

In response to the reported episodes of abuse and discrimination, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the National Urban League, signed a letter to the president of the European Union calling for fair and humane treatment for all. Last week the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs refuted allegations of discrimination by border guards and said it operated on a “first come, first served approach” that “applies to all nationalities” with priority given to women, children, and elderly people in accordance with international humanitarian law.

Ukraine’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Dmytro Kuleba, tweeted a video in early March saying an emergency hotline had been established specifically for African, Asian and other students wishing to leave Ukraine. But this doesn’t address the fact of racism or the truth that it’s too easy to overlook the incredibly devastating effect war, economic sanctions, and information blockages have on marginalized communities – in Ukraine and in Russia.

In addition to the more than 1.4 million Blacks living there, Russia is home to a large number of indigenous minorities — from the Karelians and Saami near the Finnish border to the Chukchi on the Bering Strait. In fact, There are over 100 identified ethnic groups in Russia. Of them, 41 are protected under law as legally recognized “Indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Far East.”

These groups of peoples must number fewer than 50,000 people, maintain a traditional way of life, inhabit certain remote areas of the country, and identify as a distinct ethnic group. Some groups are disqualified because of their larger populations, such as the Sakha (Yakuts), Buryat, Komi, and Khakas; others are currently striving to get recognition. Additionally, there are 24 larger ethnic groups that are identified as national identities or titular nations. These groups inhabit independent states or autonomous areas in Russia, but do not have legal protections.

When you consider the nations that are home to people of African origin, Russia is perhaps one of the last places on Earth to come to mind; yet, it is home to a population of over 70,000 Black people.

Unlike many Western countries, Russia never oppressed Black people as a singled-out group: rather, oppression was universal. While not technically slavery, serfdom, which began in 1450, evolved into near-slavery in the eighteenth century and was finally abolished in 1906. The landowner did not own the serf. In Russia the traditional relationship between lord and serf was based on land. It was because he lived on his land that the serf was bound to the lord.

World War I devastated Imperial Russia and led to the 1917 Russian Revolution. By 1919 the Bolsheviks (Communists) effectively gained control of the country. Dedicated to economically and politically transforming the nation and leading a worldwide revolution, the new Communist leadership under Joseph Stalin in the early 1920s, declared that Black people would lead the charge toward revolution in the United States. They also declared that Communists everywhere would fight to eradicate racism as well as capitalism and imperialism.

For the first time in world history, the leadership of a powerful European nation declared as its priority the elimination of racial discrimination around the world.

This increased Black America’s interest in Soviet Russia, and they migrated in two distinct groups: those attracted to and desiring to help fulfill communism’s promise of racial and social equality, and assorted artists and intellectuals lured by a welcoming totalitarian bureaucracy wanting to showcase its self-proclaimed accomplishment of anti-racism and international brotherhood. Harry Haywood, Claude McKay, James W. Ford, and Otto Huiswood were among those who arrived during the 1920s.

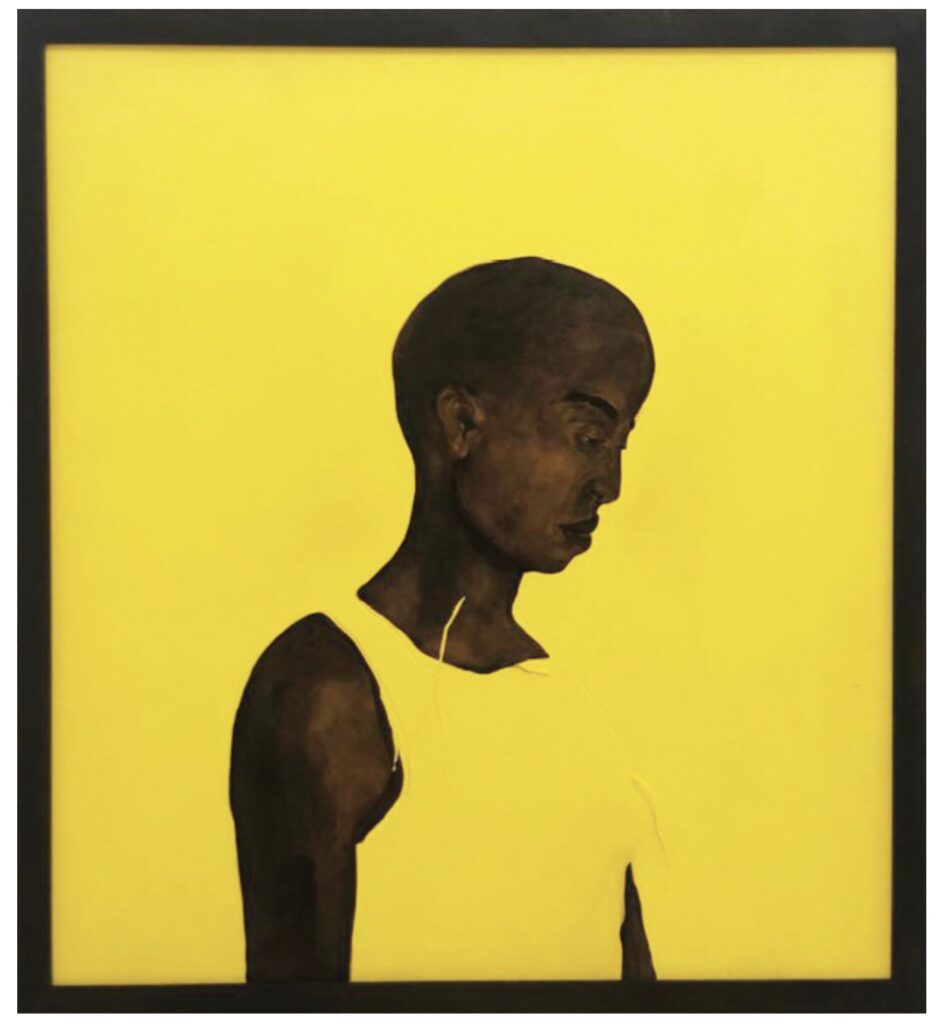

By the 1970s a new generation of Black Americans traveled to the Soviet Union. In 1979 political activist Angela Davis won the Lenin Peace Prize, traveling to Moscow to receive the honor. American conductor James Frazier led the revered Leningrad Philharmonic in concert in 1971. Playwright-novelist Alice Childress toured the USSR with members of the Harlem Writers Guild in 1971. Artist Elton Fax illustrated and published a book in 1974 recalling, among other, his recent travels in the central Asian regions of the Soviet Union. In the 1980s the Dance Theatre of Harlem was applauded in Leningrad, artists Paul Goodnight helped direct a mural project in Soviet Armenia, and Kehinde Wiley painted in a forest outside Leningrad.

While it may be easier to reduce the current war in Europe as “white,” there are Black and indigenous people on both sides of this Eurasian war. Institutional racism is a part of the identity of the United States, casual racism is part of the character of Russia and the Ukraine.

These Black Americans living the midst of a war, the vast population of Black and brown families trying to survive the constant shelling and unrelenting violence is beyond terrible. Millions of women, children, and elderly adults have been forced to flee the country with nothing but the clothes on their backs. It’s the fastest, largest forced migration of Europeans since World War II—and the crisis is truly only getting started. But European doesn’t mean white any more than American does.

The sheer scale of this human rights catastrophe must provoke action in us. It’s not their war, it’s not their fight – it’s ours. I recoil at comments about the “war over there.” The war for recognition, independence, and freedom from oppression is everywhere. It affects the lives of Black folk everywhere and if we dare to believe something that begins in a nation far removed geographically cannot touch the souls or bodies of Black people here – think on COVID.