By: Jordan Meadows

Staff Writer

The Knights of Labor (KOL)—founded in 1869 and once the nation’s largest labor organization—left an imprint on North Carolina far deeper than their brief period of prominence suggests. At their peak in the 1880s, the Knights expanded from a handful of assemblies in the Raleigh–Durham area to a statewide force stretching from Asheville to the port city of Wilmington.

The first North Carolina assemblies of the Knights of Labor formed in 1884 in the Raleigh–Durham region. Their early success was remarkable. In 1886, John Nichols—a white leader within the organization from Wake County—was elected to Congress, an early sign that labor organizing could shape political power in the South.

The first North Carolina assemblies of the Knights of Labor formed in 1884 in the Raleigh–Durham region. Their early success was remarkable. In 1886, John Nichols—a white leader within the organization from Wake County—was elected to Congress, an early sign that labor organizing could shape political power in the South.

Raleigh also became home to the KOL Cooperative Tobacco Company on East Davie Street, a worker-run enterprise that embodied the Knights’ vision of cooperative economics.

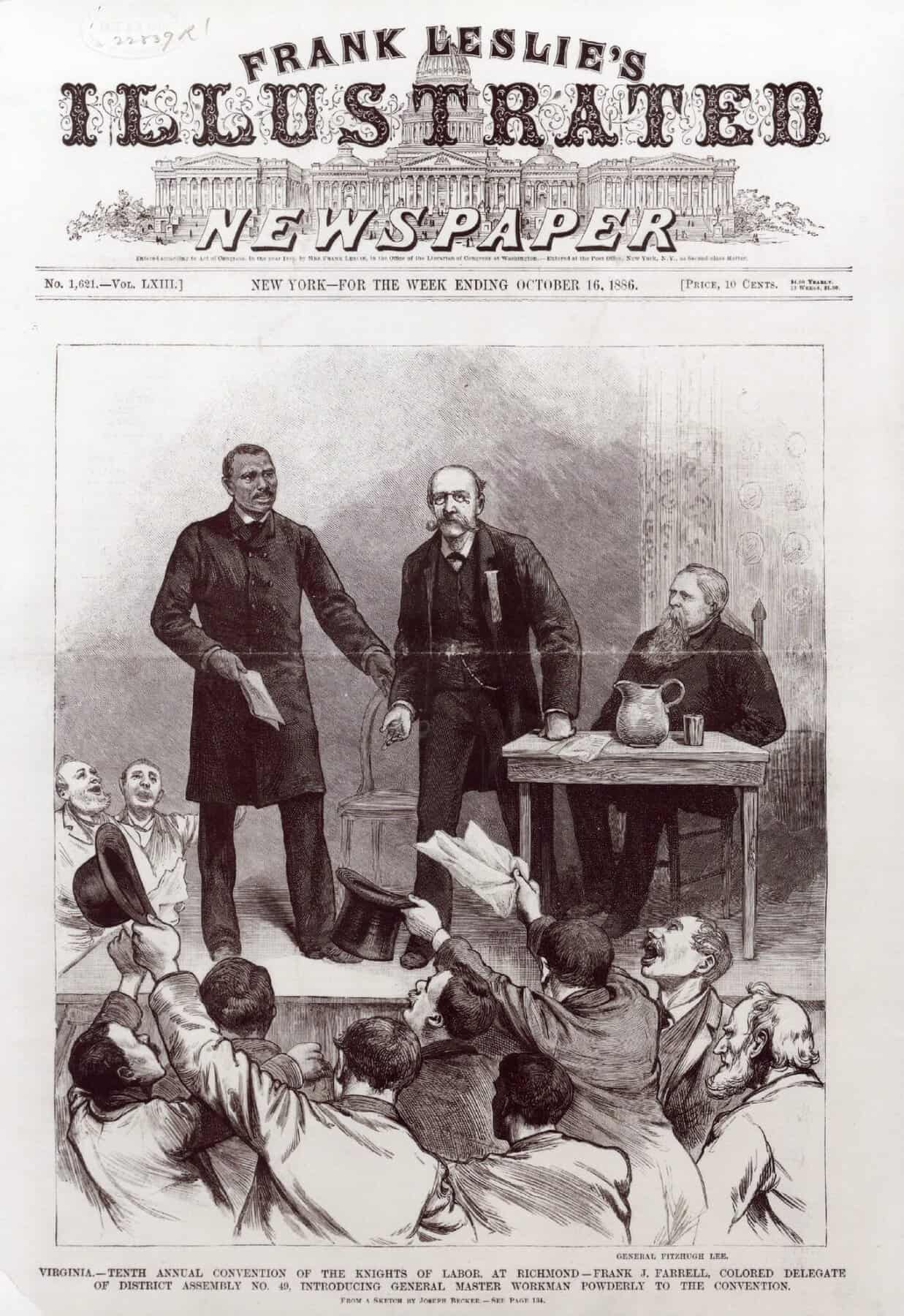

Unlike many labor organizations of the era, the Knights welcomed a broad membership. Skilled and unskilled workers, black and white, men and women were eligible, though in the South segregation often persisted in practice. Still, in North Carolina, the Knights’ interracial character became a defining feature—especially in the east.

Between 1887 and 1889, African American farm laborers in northeastern North Carolina joined the Knights in large numbers, eventually transforming the state assembly into a majority-Black body. The movement’s center of gravity shifted toward Edgecombe County, the unofficial heart of the state’s “Black Second” Congressional District.

No counties except Wake had more assemblies than Edgecombe and its neighbors Wilson and Pitt. The KOL became both a labor organization and a political engine for rural Black workers seeking economic bargaining power and political representation.

It was once reported that at New Hope Missionary Baptist Church in Swift Creek Township, about 80 workers had been meeting every Friday night for two months “waiting for someone to organize us.” The rural self-organization that sustained the Knights in eastern North Carolina—ordinary Black workers gathering in one of the county’s oldest African American churches to build a collective voice.

By 1888, Black assemblies in Edgecombe flexed their political influence. They secured the Republican nomination for Henry P. Cheatham, who became the third Black Congressman from the district. Once elected, Cheatham appointed several African American Knights of Labor leaders as postmasters—positions of both prestige and local power.

The height of the KOL’s influence in the region coincided with a rising willingness among rural laborers to challenge economic conditions directly. In 1889, farm workers mounted a three-week strike on cotton plantations in Edgecombe County. The strike did not succeed; instead, it triggered an exodus of hundreds of workers who left the county for jobs elsewhere.

Still, the Knights maintained enough strength to hold their fifth statewide convocation in Tarboro’s Opera House in January 1890. There, delegates endorsed a coalition with the Farmers’ Alliance—a partnership that evolved into the Populist Party in 1892. White farmers’ shifting allegiance to the Alliance pulled many away from the KOL, but Black Knights remained a grassroots precursor to the Republican-Populist “Fusion” coalition that would sweep North Carolina politics from 1894 to 1898.

Though the Knights of Labor faded, they seeded a tradition of worker activism that resurfaced dramatically in later decades. Tobacco workers—particularly African American women—revived mass organizing in eastern North Carolina during “Operation Dixie” in 1946. Nearly 10,000 “leaf house” workers from Virginia to Lumberton unionized, echoing the interracial, working-class solidarity the KOL had imagined. A 1947 National Labor Relations Board case involving Wilson’s Liggett & Myers stemmery documents these early efforts to secure union representation.

Today, North Carolina has one of the lowest union densities in the country. Yet the North Carolina Labor History Exhibit traces a powerful through-line of organizing, stretching from the Knights of Labor to the Duke Faculty Union in 2016. Along the way stand figures like Ella May Wiggins, murdered during the 1929 Gastonia textile strikes, and Moranda Smith, a formidable 1940s organizer who battled both economic exploitation and Jim Crow segregation.

This history also includes major victories, such as the 2008 Smithfield Foods union win, where 5,000 meatpacking workers secured representation after a long struggle, and the 2003 achievement of 8,000 farm laborers, who won the largest collective bargaining agreement in state history.

From church meetings in Edgecombe County to tobacco warehouses in Wilson, from the Black Second to Operation Dixie, the spirit of the Knights has echoed across generations.