By Jheri Hardaway

Staff Writer

Raleigh, NC - A peaceful Saturday morning in downtown Raleigh at the City of Raleigh Museum was the perfect venue for a powerful Emancipation Day celebration. In addition to the usual historical reverence, the atmosphere was charged with a reimagining of the American narrative. Guest speaker Antwain K. Hunter, UNC Chapel Hill Assistant Professor in the Department of History, delivered a prolific and challenging lecture on the history of Emancipation Day, a day he argues is one of the most "revolutionary moments" in a nation that prides itself on revolution, yet one that remains insufficiently celebrated across the country. For those of us who value transparent history and the execution of memorable experiences, Hunter’s talk was a masterclass in intellectual honesty. He pushed the audience to look past the "Great Emancipator" trope and recognize emancipation as a messy, bottom-up process driven as much by enslaved people themselves as by the man in the White House.

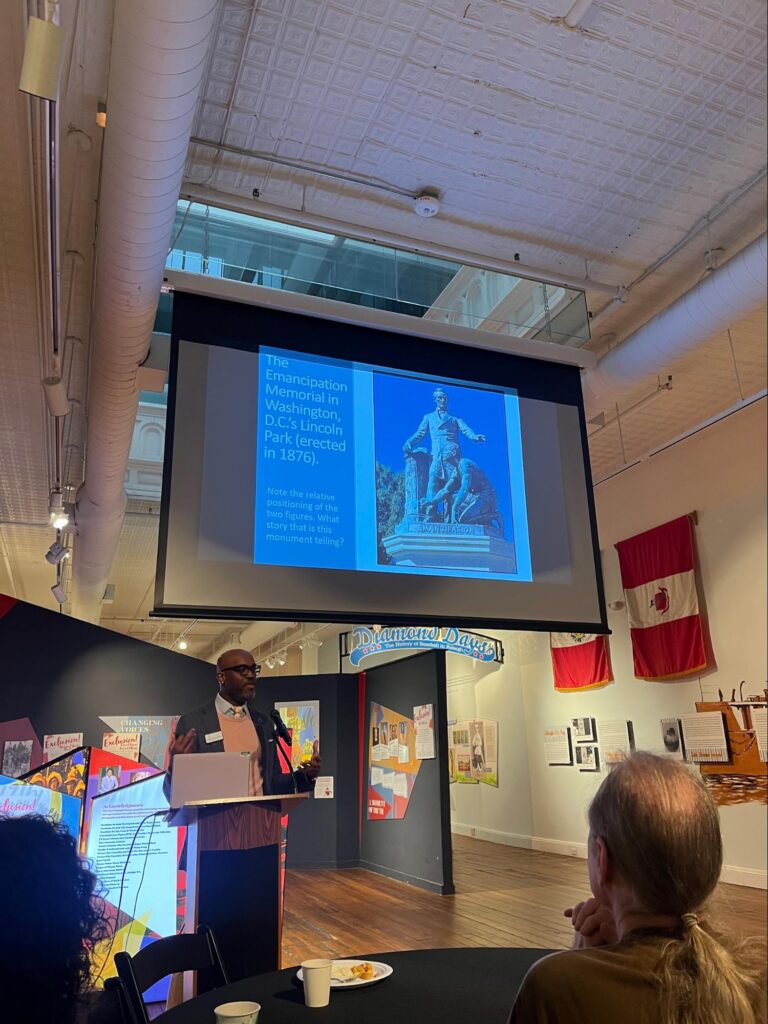

Hunter began by addressing the popular imagery of emancipation: President Abraham Lincoln standing over a kneeling enslaved man, bestowing freedom with a signature. While Hunter admitted Lincoln is among his favorite presidents, he was quick to hold him to account. "Lincoln’s initial wartime goal, of course, was to preserve the Union," Hunter explained. Early in the conflict, Lincoln was famously cautious, tethered by constitutional constraints and the desperate need to keep the "border states" (slave states that hadn't seceded) loyal to the Union. In his 1861 inaugural address, Lincoln explicitly stated he had no lawful right or inclination to interfere with slavery where it already existed. However, the "revolutionary moment" wasn't waiting for Lincoln to catch up. It was already happening in the muddy camps and fortresses of the South.

To the “Contraband of War” or those we now refer to as the enslaved, freedom appeared as a military necessity. The shift toward freedom began with bold military officers and even bolder "freedom seekers." Hunter highlighted General Benjamin Butler at Fort Monroe, Virginia. In May 1861, just a month into the war, three enslaved men fled to the fort. When their enslaver came to reclaim them under the Fugitive Slave Law, Butler (a lawyer by trade) refused. He classified the men as "contraband of war," arguing that if they were "property" being used to aid the Confederacy, the Union had every right to seize them. This sparked a wave. Within months, thousands of enslaved people from Virginia and Eastern North Carolina were heading toward Union lines, effectively forcing the federal government to create a policy where none existed.

When the Emancipation Proclamation finally took effect on January 1, 1863, it was, as Hunter noted, a strategic "war measure." It was limited in scope, exempting the border states and areas already under Union control. Yet, its symbolic and practical power was undeniable. In North Carolina alone, as many as 10,000 enslaved people sought refuge in New Bern once the Union Army established a foothold. The Proclamation also opened the doors for Black enlistment. It is believed that 180,000 Black men served in the Union Army, while 18,000 Black men served in the Navy, many of them "Blackwater" men from the coast of North Carolina. These men weren't just recipients of freedom; they were its primary defenders.

The lecture concluded with a vibrant Q&A session that touched on the "pragmatism" of the Black experience—from the use of firearms for self-defense and hunting in the North Carolina swamps to the vital role of the Black church in building schools and hospitals post-1865. Hunter’s message was clear: Emancipation is not just Black history or Southern history; it is the moment the United States became a "free country" for the first time in its existence. It was a victory achieved through the collaboration of radical lawmakers, military officers, and, most importantly, the everyday individuals who seized their own liberty. As we look toward the future of Raleigh and the upcoming "America 250" celebrations, let us remember Antwain K. Hunter’s call to appreciate the "fullness" of our history—the fireworks and the struggles alike.