By Jordan Meadows

Staff Writer

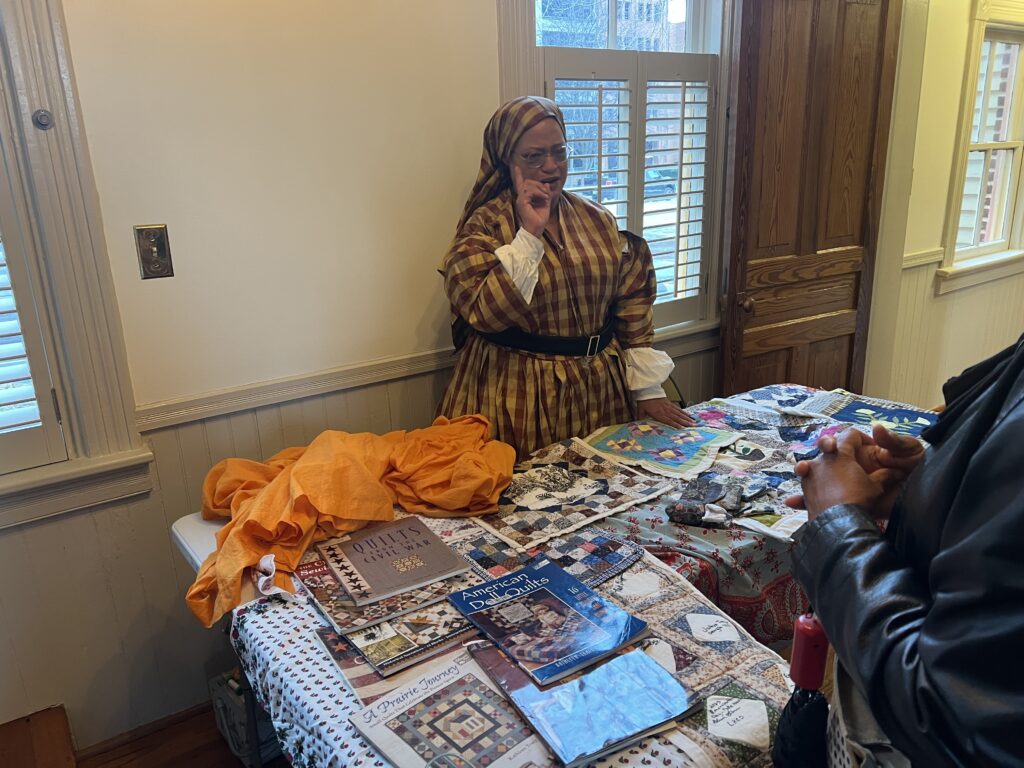

To celebrate Emancipation Day, the Pope House Museum on S. Wilmington Street in Raleigh, North Carolina, presented “Fighting for Freedom: Black Civil War Reenactors” on Saturday. The free event brought history to life as reenactors portrayed United States Colored Troops (USCT) and their allies, sharing the incredible stories of Black soldiers and their lives both in the camps and on the front lines.

During the Civil War, Black soldiers were primarily commanded by white officers, and Black officers were generally forbidden from leading white troops. While Black soldiers could rise to non-commissioned officer ranks, such as sergeant or lieutenant, instances of them commanding white soldiers were extremely rare and temporary, usually only occurring in emergencies if all other officers were killed or incapacitated. Martin Delany, for example, became the first officially commissioned Black major in the U.S. Army, leading the 55th Massachusetts, but he never officially commanded white troops.

By the end of the war, thousands of Black men from North Carolina had joined the USCT, with units including the 1st and 2nd North Carolina Colored Volunteers (later the 35th and 36th U.S. Colored Infantry) and the 37th and 38th US Colored Infantry, many recruited from eastern North Carolina. These regiments were composed largely of formerly enslaved men, whose local knowledge and personal stakes fueled their determination.

The USCT in North Carolina guarded supply lines, forts, and railroads and participated in combat, including raids and battles around Wilmington, Goldsboro, and the coastal regions. In the Battle of Town Creek (1865), USCT regiments helped defeat the last pockets of Confederate resistance in the area.

Beyond combat, USCT soldiers performed essential work behind the scenes. They prepared meals in field kitchens, baked bread, cooked stews, and preserved food for long marches. They foraged for supplies, transported rations, ammunition, and equipment to frontline units, and constructed forts, camps, trenches, and defensive positions.

USCT units also repaired roads and bridges, maintained picket lines and guard posts, assisted in hospitals as orderlies, and worked in specialized engineering and labor battalions repairing railroads, telegraph lines, and water systems. Maintaining camp hygiene, digging latrines, and collecting firewood were critical tasks to prevent disease and keep the army functional.

Black women also played a vital, though often less visible, role in the Union war effort. They worked as spies and scouts, gathering intelligence on Confederate troop movements, and as nurses and cooks in hospitals and army camps. Many served as guides for escaping enslaved people or helped Union forces navigate occupied territories.

One of the most famous of these women was Harriet Tubman, who gathered intelligence on Confederate positions, led reconnaissance missions behind enemy lines, and collaborated with Union commanders to plan raids and assaults, particularly in coastal and swamp areas.

Together, the contributions of Black soldiers and women during the Civil War, both in combat and behind the scenes, were critical to the Union victory and the enforcement of emancipation. This event at the Pope House Museum offered a unique opportunity to hear the stories and honor the bravery and resilience of those who fought for freedom.