By Jordan Meadows

Staff Writer

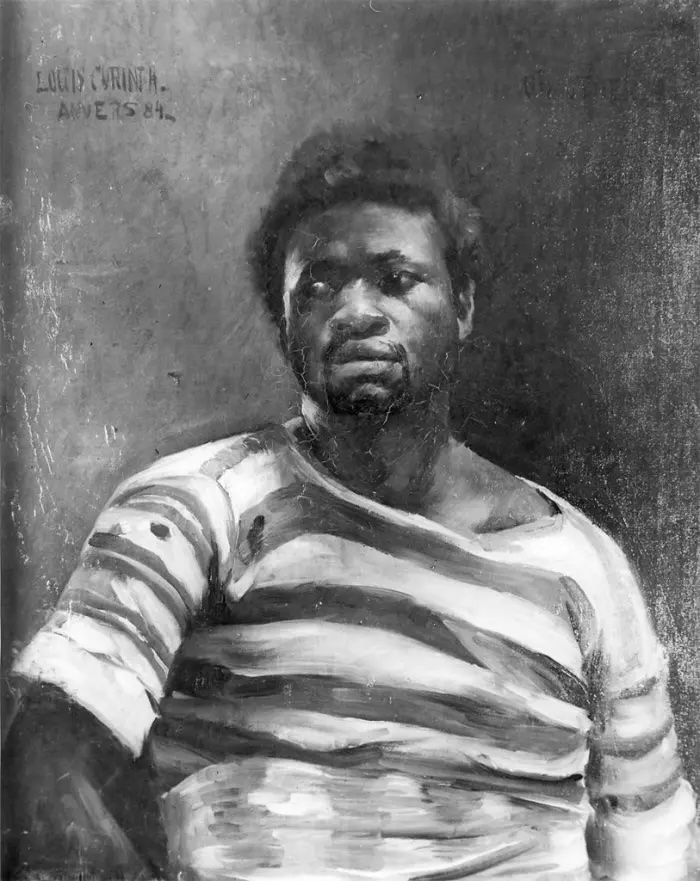

Moses Grandy was a Black abolitionist, seaman, and author born into slavery around 1786 in Camden County, North Carolina.

As Grandy recounted in his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Moses Grandy; Late a Slave in the United States of America, he did not know his exact birth date—a reality for many enslaved people, whose births were rarely recorded.

His first enslaver, Billy Grandy, was a harsh, alcoholic man who shattered Moses’ family by selling all of his siblings, despite promising their mother he would not. When she protested, she was flogged. Moses, the only child left with her, watched helplessly as his family was torn apart—a trauma that remained with him for the rest of his life.

At age eight, Moses was passed on to Billy Grandy’s son, James Grandy, a boy close to his age and his childhood playmate. By age ten, Moses was being hired out annually to various men, beginning a cycle of abuse, exploitation, and survival. His second temporary master, Jemmy Coates, beat him so severely with a sapling that it broke off in his side. Another man, Enoch Sawyer, starved him so badly that Grandy had to grind cornhusks into flour just to eat.

At age eight, Moses was passed on to Billy Grandy’s son, James Grandy, a boy close to his age and his childhood playmate. By age ten, Moses was being hired out annually to various men, beginning a cycle of abuse, exploitation, and survival. His second temporary master, Jemmy Coates, beat him so severely with a sapling that it broke off in his side. Another man, Enoch Sawyer, starved him so badly that Grandy had to grind cornhusks into flour just to eat.

By his teens, Moses was managing ferry crossings in Camden and later working on canal boats. He became part of a labor force that built the Great Dismal Swamp Canal. But this work also marked the beginning of a new chapter: he became a skilled navigator and eventually a captain of freight boats running goods between Elizabeth City, North Carolina, and Norfolk, Virginia.

During this time, Grandy’s ability to earn money improved, particularly when he worked for Charles Grice, his enslaver’s brother-in-law. Although still under enslavement, the work offered better food, clothing, and a share of earnings.

Hoping to buy his freedom, Grandy arranged to pay his enslaver $600—a large sum at the time. But after accepting the money, James betrayed him and sold him to another enslaver.

This was the first of two heartbreaking betrayals: Trewitt later sold Moses again just before he was to complete his second freedom payment. His new enslaver quickly sold him back to the same cruel man who had abused him as a child. It was under Sawyer that Moses married a second time, although their union, like so many others among the enslaved, was legally unrecognized.

Despite the immense setbacks, Grandy never gave up. He struck an agreement with Minner, a canal operator who bought Moses with the understanding that he would repay the cost over time. Grandy worked tirelessly for three years and finally earned his freedom on the third attempt.

Fearing re-enslavement, especially after Minner's death, Moses fled to Boston, where he took work in coal yards and later served as a seaman aboard the ship James Murray, earning the same wages as white sailors. With the $300 he saved, he bought his wife’s freedom and continued working to purchase the freedom of his children and grandchildren.

Grandy’s personal life was filled with tragedy. His first wife, whom he described as the love of his life, was sold just eight months after their marriage. As he poled a boat down the river, he heard her call out to him—she was a slave being shipped south. He never saw her again.

In total, Grandy had six children, many of whom were sold into slavery. Two daughters eventually bought their own freedom. Moses also sought to purchase the freedom of four grandchildren, whose price totaled $2,400—a monumental sum in the mid-1800s.

His attempts to track down and liberate his extended family were hindered by the cruel anonymity of slavery. Enslaved people had no legal surnames, and relatives were often scattered across plantations, towns, and states, impossible to trace.

In 1842, Grandy traveled to London, where he collaborated with George Thompson, a British antislavery activist affiliated with William Lloyd Garrison and the New England Anti-Slavery Society. As Grandy was illiterate, he dictated his life story to Thompson, resulting in the publication of his narrative in 1843. The book served both as an abolitionist tool and a fundraiser to help Grandy purchase the freedom of remaining family members.\

The Narrative of the Life of Moses Grandy was reprinted in three American editions in 1844 and widely circulated in the U.S. and Britain. It joined a growing body of slave narratives that provided vital first-hand testimony of slavery’s brutality, helping to galvanize the abolitionist movement. Despite criticism from some contemporaries and modern skeptics, much of Grandy's account—such as the use of salt water on wounds, the separation of families, and harsher treatment after Nat Turner's 1831 revolt—has been corroborated by independent historical sources.

According to a descendant, Grandy saved the equivalent of $101,000 in today's currency over the course of his life—money he used not for comfort, but to buy freedom for those he loved.

Though little is known of Grandy’s final years or death, his impact endures. In 2006, a portion of Virginia State Route 165 was renamed the Moses Grandy Trail in his honor, cementing his place in American history.

In the words of abolitionist George Thompson, those who met Grandy found his “benevolence, affection, kindness of heart, and elasticity of spirit…truly remarkable.” And over 180 years later, his voice still speaks—urging us to strive for justice.