By Jordan Meadows

Staff Writer

A community meeting titled ‘Fertility and Reproductive Health in the Black Community’, held at the Wake County Public Library in Raleigh last Tuesday, brought together healthcare professionals, advocates, scholars, and community members to address an increasingly urgent public health crisis: the disparities in fertility and maternal health outcomes experienced by Black women in North Carolina and across the United States.

The meeting was a collaboration between the Black Pearls Society, Wake County Government, and the Wake Area Health Education Center, and the London Women’s Health Clinic, aiming to provide education and support.

A study conducted between 2014 and 2019 by the NIH revealed that the prevalence of gynecological conditions such as uterine fibroids and tubal damage disproportionately affects Black women. Black patients reported a significantly higher rate of tubal factor infertility—31%—compared to the national average of 18%. Uterine fibroids, in particular, can block fertilization or impede sperm from reaching the egg, often going undiagnosed or untreated for years.

The average age at which Black women begin fertility treatment is also higher than the national average by about one year—a critical delay given that fertility declines with age. For single Black patients, that starting point is even later, often around age 38. These delays are frequently attributed to a lack of health insurance, healthcare access, family support, and persistent cultural stigma around infertility and reproductive health in communities of color.

“Lots of women, especially in the Black community, encounter pain or struggle with conception but wait too long to seek help,” one speaker noted. “They may not have support systems, insurance, or even know what’s wrong. By the time they come in, the clock has already been ticking.”

Treatment for infertility typically starts with diagnostic procedures such as a pelvic ultrasound and blood tests. Interventions range from lifestyle changes and timed intercourse to more advanced options like intrauterine insemination (IUI), egg freezing, in vitro fertilization (IVF), and, when necessary, the use of donor gametes or surrogacy.

To address the emotional toll and isolation of fertility struggles, groups like the Black Women’s Fertility Group have emerged, offering community education and support to Black women navigating these challenges.

Dr. Arthi Thangavel, a fertility specialist and Clinical Director at the Cambridge branch of the London Women’s Health Clinic, joined the meeting virtually from the UK in honor of Black History Month, which is observed in October in the United Kingdom. She emphasized the need for global cooperation and understanding around racial disparities in reproductive health.

“We are seeing similar patterns across the Atlantic,” she said. “It’s not isolated to one country—it’s a structural issue that transcends borders.”

Deena Hayes-Greene, co-founder of the Black Pearls Society, offered a stark reminder of the broader implications.

“The ability to reach your first birthday tells us something about the climate for Black well-being, period. Babies are dying. Mothers are dying. Resourced or not, something in this environment says that being Black is bad for your health.”

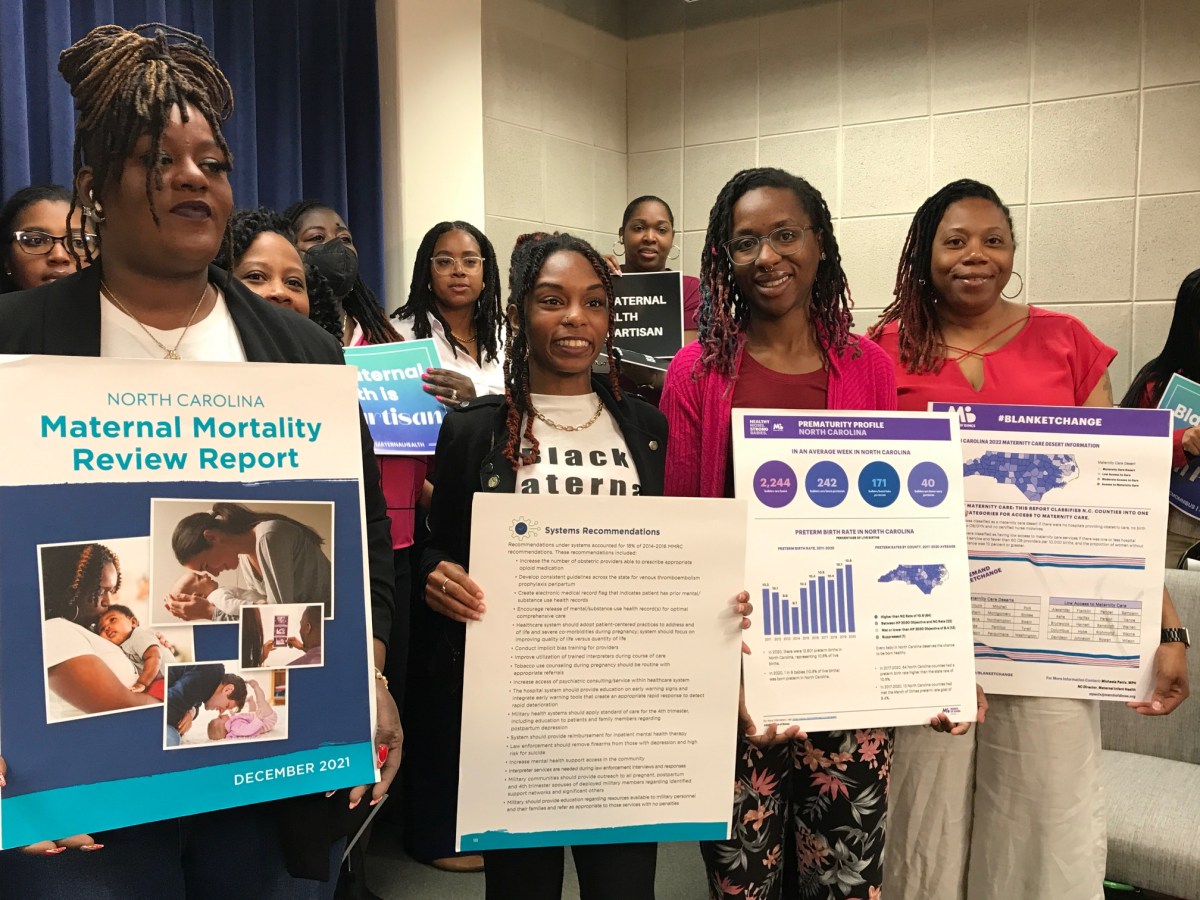

Black women in the United States face maternal mortality rates three to four times higher than non-Hispanic White women. In North Carolina, that disparity is even more pronounced. From 2020 to 2022, Black women accounted for 43% of pregnancy-related deaths in the state despite making up just 22% of the population.

A recent report found that 39.1% of Black women received late or no prenatal care, compared to 23.9% of White women. Nearly 9% of Black women of childbearing age in North Carolina lacked health insurance as of late 2023, although Medicaid expansion may help alleviate that—if it remains funded amid ongoing political gridlock.

“We are doing a better job as a society to talk about understanding the impact of systems and structures,” said Dr. Stephanie Baker, co-chair of the conference and Associate Professor of Public Health at Elon University.

Governor Josh Stein proclaimed April 3, 2025, as Black Maternal Health Week in North Carolina, a symbolic step toward addressing the crisis. State lawmakers are currently debating Senate Bill 838, known as the “MOMnibus” bill. The legislation would provide $5 million for initiatives, including implicit bias training for healthcare providers, funding for perinatal education, and improved data collection on maternal mortality causes.

The urgency is underscored by data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which shows the U.S. maternal mortality rate in 2021 reached 32.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, up from 20.1 in 2019. In North Carolina, the figure was even more dire—44 deaths per 100,000. More than 80% of these deaths were preventable.

The crisis doesn't end with mothers. North Carolina ranks 10th worst in the nation for infant mortality. Black babies are more than twice as likely to die before their first birthday as White babies. In some rural counties, especially in the northeast and southeast regions of the state, maternity care is almost nonexistent.