By Jordan Meadows

Staff Writer

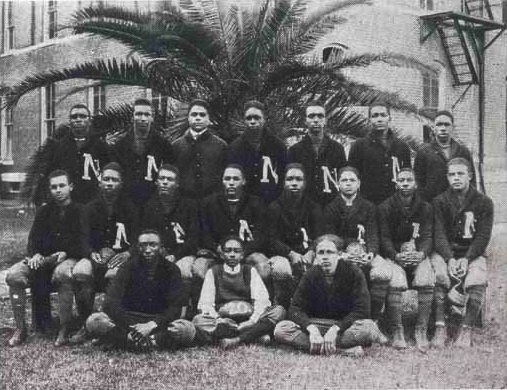

The roots of HBCU football trace back to December 27, 1892, when Biddle College, now Johnson C. Smith University, defeated Livingstone College in what is recognized as the first intercollegiate football game between two Black institutions. Played on the snowy lawn of Livingstone’s campus in North Carolina, the game was organized with minimal resources: uniforms sewn by students, cleats added to street shoes, and a football purchased collectively by the teams.

In the early decades of college football, segregation barred most HBCUs from competing against predominantly white institutions. As a result, Black colleges were largely confined to playing one another and developing their own systems to determine champions.

In the early decades of college football, segregation barred most HBCUs from competing against predominantly white institutions. As a result, Black colleges were largely confined to playing one another and developing their own systems to determine champions.

The earliest documented claim of an HBCU national championship dates to 1906, when Livingstone College, led by captain Benjamin Butler “Ben” Church, declared itself the best team in Black college football. By the 1920s, more formal efforts emerged. Other initiatives, including the Champion Aggregation of All Conferences, reflected growing efforts within the HBCU community to assert legitimacy and structure in the absence of access to mainstream college football power brokers.

The gradual dismantling of segregation after World War II opened limited new doors. A milestone came in 1948, when Southern University defeated San Francisco State in the Fruit Bowl, marking one of the first prominent victories by an HBCU over a predominantly white institution. In the 1950s, many HBCUs gravitated toward the NAIA, which was more welcoming to smaller schools and institutions of diverse demographics.

Eventually, most HBCUs transitioned into the NCAA, competing across multiple divisions while continuing to crown Black national champions alongside NCAA and NAIA titles.

Throughout this period, HBCU programs produced dominant teams, legendary coaches, and future professional stars: Florida A&M and Tennessee State each claimed 16 HBCU national championships, while Central State won five consecutive titles from 1986 to 1990. Coaching icons such as Eddie Robinson at Grambling State, John Merritt at Tennessee State, and Rod Broadway helped elevate HBCU football to national prominence. On the field, programs like Southern, Prairie View A&M, Tuskegee, and North Carolina A&T achieved perfect seasons.

Efforts to stage postseason showcase games have been a recurring theme in HBCU history. Early attempts included the Steel Bowl, Vulcan Bowl, National Bowl, and National Football Classic, though none achieved lasting stability.

A breakthrough finally came in 2015 with the creation of the Celebration Bowl. Contested annually between the champions of the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference (MEAC) and the Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC), the Celebration Bowl has become the de facto national championship of Black college football.

Played in Atlanta and currently hosted at Mercedes-Benz Stadium, it stands as the only active bowl game featuring teams from the NCAA Football Championship Subdivision. North Carolina A&T has emerged as the game’s most successful program, winning four championships since its inception.

Because it is played during the FCS playoffs, MEAC and SWAC champions do not participate in the postseason tournament, a tradeoff that reflects the bowl’s cultural significance and national visibility.

A total of 27 Pro Football Hall of Famers played their college football in the MEAC or SWAC, including legends such as Walter Payton, Jerry Rice, and Willie Lanier. In recognition of that legacy, the Black College Football Hall of Fame has become a central institution promoting the history of the sport. Its latest initiative: the HBCU Legacy Bowl. The all-star game showcases NFL draft-eligible HBCU players and is held during Black History Month.