By Jordan Meadows

Staff Writer

On January 22, 1834, a violent confrontation at the Walnut Creek plantation in Edgecombe County, North Carolina, would lead to one of the most significant legal decisions in the antebellum South.

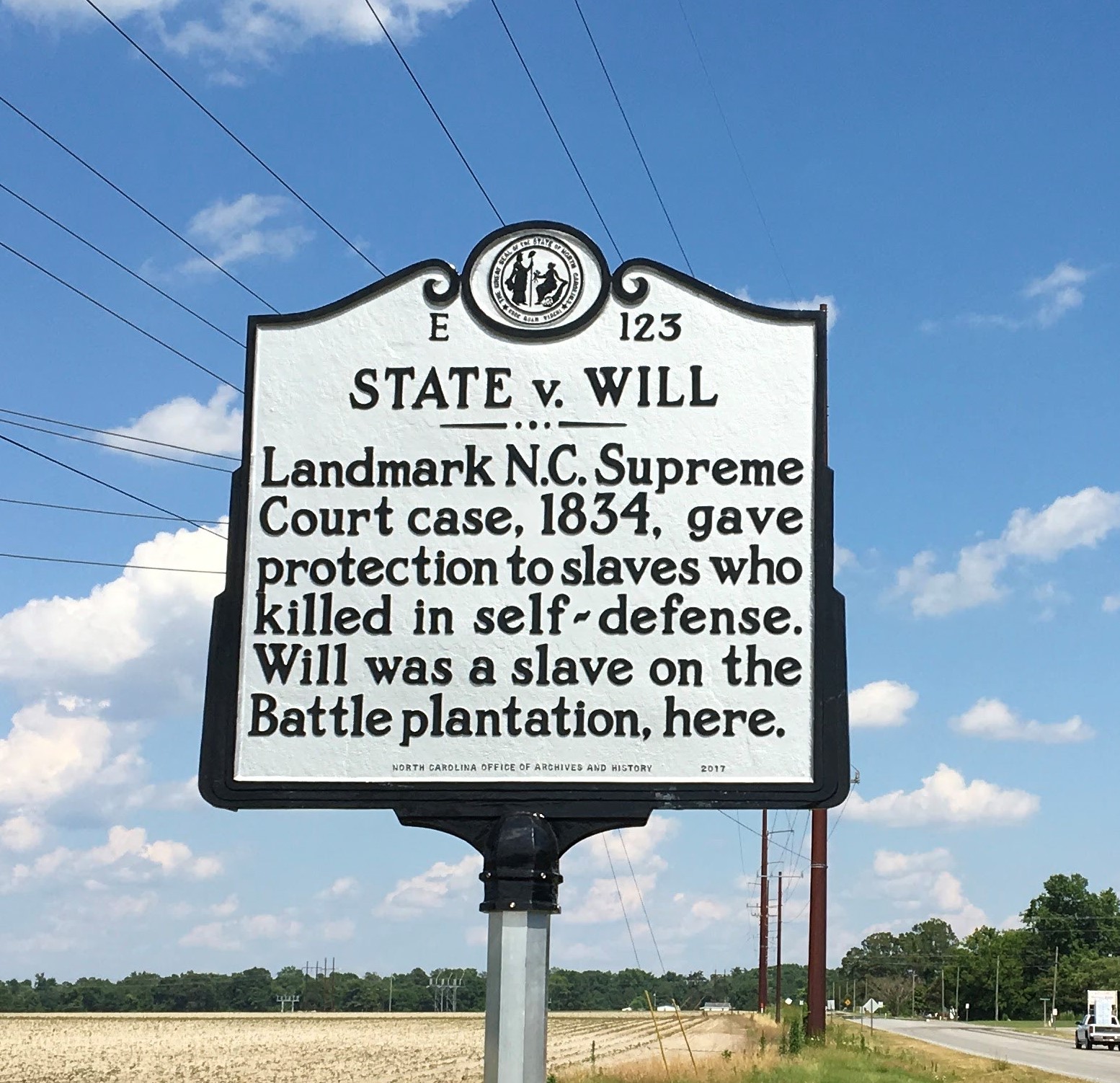

Will, an enslaved man owned by James S. Battle, became the center of the landmark case State v. Will, which challenged the legal framework of slavery and recognized, however narrowly, the moral agency of enslaved people.

The North Carolina Supreme Court’s unanimous decision, written by Justice William Gaston, declared that an enslaved person acting in self-defense under extreme provocation could not be convicted of murder, but only of manslaughter. This ruling stood in direct contrast to the earlier State v. Mann (1829) decision, which had granted masters absolute and unchallengeable authority over slaves.

The North Carolina Supreme Court’s unanimous decision, written by Justice William Gaston, declared that an enslaved person acting in self-defense under extreme provocation could not be convicted of murder, but only of manslaughter. This ruling stood in direct contrast to the earlier State v. Mann (1829) decision, which had granted masters absolute and unchallengeable authority over slaves.

The chain of events began with a dispute over a simple farm tool—a hoe. Will had crafted the handle in his own time and considered it his personal possession. When the foreman instructed another slave to use it, an argument erupted. Will, angry at what he saw as an affront to his limited autonomy, broke the handle and left to work at a nearby cotton screw.

The foreman informed Richard Baxter, the overseer, who armed himself with a shotgun and ordered Allen to follow with a whip. Upon confronting him, Baxter ordered Will down from the cotton screw. Will obeyed humbly, but as Baxter advanced, Will attempted to flee. Baxter shot him in the back from close range, wounding him severely. Despite his injuries, Will managed to escape into the woods, only to be overtaken by Baxter. In the desperate struggle that followed, Will, armed with a knife, inflicted several wounds on Baxter, including a deep gash to his arm that would prove fatal.

The next day, Will returned voluntarily to the plantation, unaware that Baxter had died of blood loss. He was charged with first-degree murder.

The Edgecombe County Superior Court found him guilty and sentenced him to death. His owner, James Battle, believed that Will had acted in self-defense and, in an extraordinary gesture for the time, hired two of North Carolina’s most prominent lawyers, Bartholomew Figures Moore and George Washington Mordecai, to appeal the case. Battle paid Moore an astonishing $1,000 to ensure that Will received a fair defense.

The appeal reached the North Carolina Supreme Court in December 1834. The defense argued that the law should recognize the humanity of the enslaved and that absolute power over another human being was “irresponsible power.” Moore directly challenged Chief Justice Thomas Ruffin’s earlier ruling in State v. Mann, which had declared that “the power of the master must be absolute, to render the submission of the slave perfect.”

Although the court did not overturn Mann outright, Justice William Gaston’s opinion marked a profound departure. Writing for a unanimous court, Gaston reasoned that Will’s act was not one of “diabolical malice,” but of human passion and self-preservation. He declared that it was “instinctive to fly, human to struggle,” and that “terror or resentment, the strongest of passions, had given the struggle its fatal issue.”

Gaston’s opinion openly recognized the enslaved as moral and sentient beings. “The prisoner,” he wrote, “is a human being, degraded indeed by slavery, but yet having organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions, like our own.” The court ruled that Will’s actions, though unlawful, were not murder. Instead, the killing arose out of “a brief fury” and should be classified as manslaughter. As a result, Will’s death sentence was overturned.

He was eventually released and sent to another of Battle’s plantations in Mississippi.

In the 1830s, North Carolina was a slaveholding state grappling with its own contradictions. Slaves were both “persons” and “property,” their legal status forcing courts to reconcile human rights with economic interests.

State v. Will did not usher in sweeping reform. Slavery continued for three more decades, and most enslaved people in the South would never see justice in a courtroom. But the case marked an essential moment in North Carolina’s legal evolution. Abolitionists and moderate reformers alike praised the decision, and legal scholars later cited it as a precedent for limiting the excesses of masterly power.

In 2016, the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources (DNCR) installed a historical marker along US 64 Alternate at Dunbar Road, northwest of Tarboro in Edgecombe County, in recognition of the case. The marker stands on the site of the former plantation.