By Jordan Meadows

Staff Writer

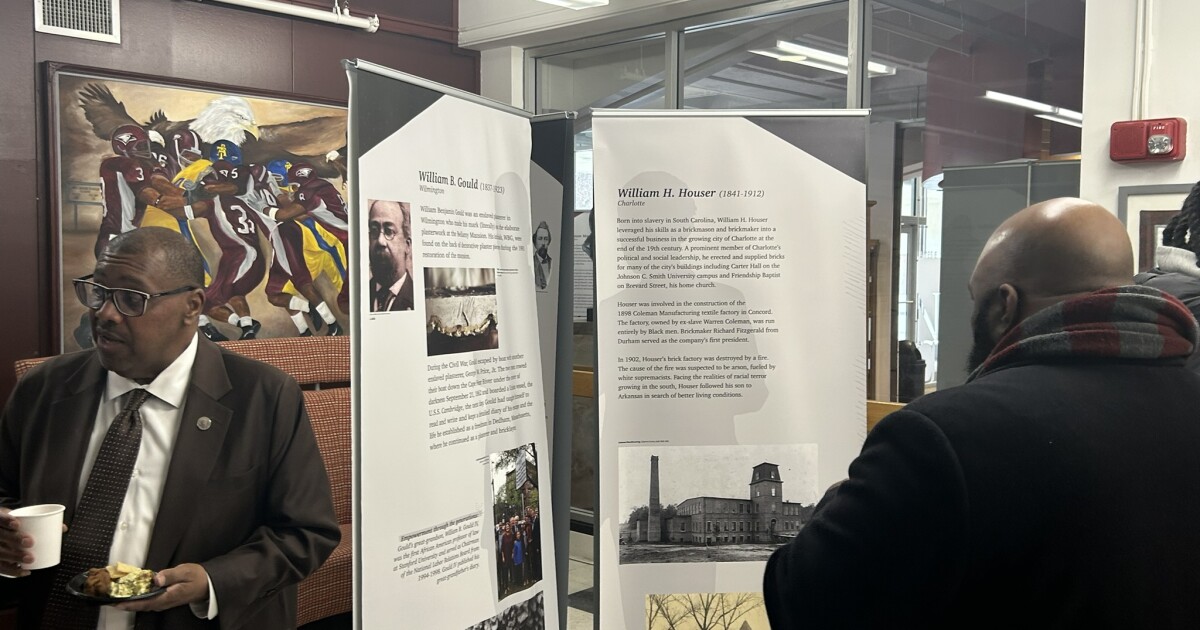

At North Carolina Central University’s James E. Shepard Memorial Library, a bold banner greets visitors with three simple words: “We Built This.”

Beneath it, the exhibit explains, “Many of the historic buildings we revere in North Carolina are credited to their owners. Rarely are the people responsible for the labor and craftsmanship recognized. This exhibit seeks to acknowledge the countless African Americans who built the historic buildings we collectively treasure.”

The traveling exhibit, “Profiles of Black Architects and Builders in North Carolina,” was created by Preservation North Carolina and is being presented in Durham by Hayti Promise Community Development Corporation and Preservation Durham. It marks the first time NCCU has hosted the exhibit, which is part of the university’s Black History Month event series.

Spanning three centuries, the exhibit features more than two dozen profiles of Black architects, builders and craftsmen—from enslaved people whose African construction knowledge shaped early Southern architecture, to post–Civil War tradesmen who built schools and churches, to civic leaders of Durham’s Black Wall Street and contemporary design professionals. Through personal stories and historic photographs, it explores pivotal eras including slavery and Reconstruction, the founding of historically Black colleges and universities and Black churches, Jim Crow and segregation, and the rise of Black civic leaders and professionals.

“The NCCU James E. Shepard Memorial Library is proud to host the ‘We Built This’ exhibition, a virtual encyclopedia of African American architects and builders whose work has shaped North Carolina’s towns, churches, businesses, HBCU campuses, and neighborhoods for generations,” said André Vann, university archivist and public history instructor. “Through the design and construction of both public and private spaces, the exhibit honors their skill, creativity, and lasting impact.”

“The NCCU James E. Shepard Memorial Library is proud to host the ‘We Built This’ exhibition, a virtual encyclopedia of African American architects and builders whose work has shaped North Carolina’s towns, churches, businesses, HBCU campuses, and neighborhoods for generations,” said André Vann, university archivist and public history instructor. “Through the design and construction of both public and private spaces, the exhibit honors their skill, creativity, and lasting impact.”

Among the figures highlighted is W. Edward Jenkins, a Wake County native who served in World War II and studied architectural engineering at North Carolina A&T State University, Class of 1949. Jenkins became the first Black architect hired by a previously all-white firm in Greensboro and was licensed in North Carolina in 1953. His work includes NCCU’s LeRoy T. Walker Physical Education and Recreation Complex, the Albert L. Turner Law Building, and, in 1977, the contemporary White Rock Baptist Church.

The exhibit also spotlights Julian Francis Abele, chief designer of Duke University’s West Campus, including the iconic Duke Chapel. Abele was the first Black graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design in 1902. One of his early credited works was Cameron Indoor Stadium in 1938. He died 11 years before Duke admitted its first Black student.

Other profiles include William H. Houser, a formerly enslaved man from South Carolina who went on to build facilities such as Carter Hall at Johnson C. Smith University; John Merrick, founder of North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company and a pillar of Durham’s Black Wall Street; Bishop Henry Beard Delany, who oversaw construction of the campus at Saint Augustine’s University; and John Winters, a builder who became the first African American elected to Raleigh’s City Council.

The exhibit reaches into the 20th and 21st centuries, highlighting the Rosenwald school-building movement that resulted in more than 800 schools across North Carolina, post–World War II Black builders and pioneers such as Danita Brown, who in 1990 became the first Black woman licensed to practice architecture in North Carolina–one of only 30 Black women licensed in the United States at the time. Brown now serves in national historic preservation leadership roles at the federal level.

The exhibit also explores the role of fraternal organizations and tradesmen in the late 19th century, including Black Freemasons who established 11 lodges across the state by 1873 and formed the North Carolina Industrial Association in 1879 to promote Black economic welfare in the South. The association organized the Colored State Fair from 1879 to 1930, a showcase of Black enterprise and craftsmanship.

Students say the exhibit is already reshaping their understanding of history. Whitaker, a 19-year-old sophomore history major at NCCU, said learning about the builders behind familiar landmarks changed his perspective.

For Black architects and builders working today, the exhibit carries professional and personal significance. Fredrick Davis, a Durham architect and builder of public school facilities, called the history essential.

“It brings me great joy to see the pioneers who came before me, and it encourages me to continue in that effort,” Davis said. “For centuries, as architects and builders, we have been responsible for highlighting and improving the built environment.”

Cheryl Brown, board chair of Hayti Promise Community Development Corporation, said the exhibit resonates deeply with Durham’s Hayti District, once a thriving center of Black enterprise.

“By recognizing the profound impact of the craftsmen, professionals, and civic leaders featured in this exhibit, we are reminded of what made the Hayti District vibrant and successful.”