By: Jordan Meadows

Staff Writer

North Carolina has long been at the center of national debates over gerrymandering. Despite regularly electing Democrats to statewide offices, Republicans have consistently secured a disproportionate share of congressional and legislative seats.

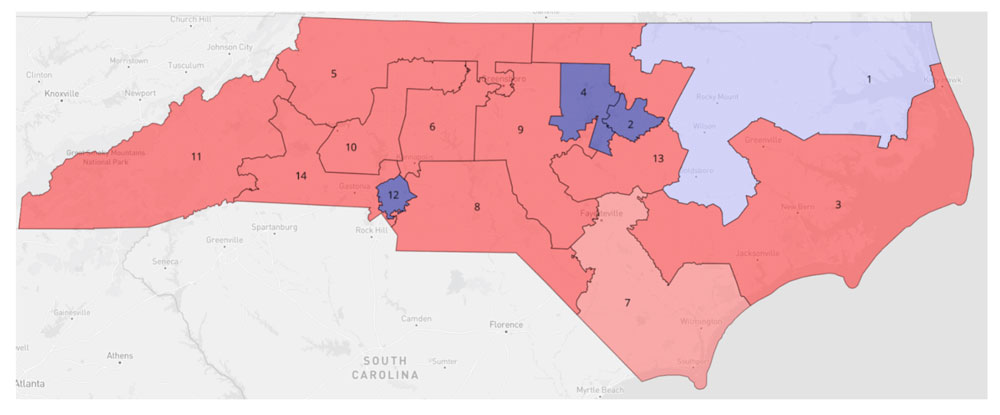

The Cook Political Report, for example, projects Republicans will safely win 10 out of 14 House seats in 2026—a result many observers attribute not to voter preference but to the drawing of electoral maps.

Gerrymandering, the deliberate manipulation of electoral district boundaries to benefit a particular political party, has played a defining role in shaping North Carolina's political landscape. In North Carolina, the state legislature—currently controlled by Republicans—draws both its own districts and the state’s congressional map. Legal and political developments over the last several years have significantly limited the ability of courts to challenge these maps, especially when claims are based on partisan advantage rather than racial discrimination.

The current legal landscape was shaped by several major court decisions. In Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable in federal court, meaning such cases cannot be decided by the judiciary. Though the Court acknowledged that excessive partisan gerrymandering was "incompatible with democratic principles," it concluded that the issue must be addressed by Congress or state governments.

At the state level, the North Carolina Supreme Court initially found partisan gerrymandering to be unconstitutional in Harper v. Hall. However, after a shift in the court’s ideological composition following the 2022 elections, that ruling was overturned in April 2023. The court's new Republican majority determined that partisan gerrymandering was a political question not subject to judicial review, aligning state law with the precedent set by Rucho.

With partisan gerrymandering effectively immune from legal challenge in North Carolina, some have turned their focus to racial gerrymandering, which remains justiciable under the U.S. Constitution and the Voting Rights Act. Plaintiffs in Williams v. Hall—a consolidated lawsuit brought by the NAACP, Common Cause, and others—are currently challenging North Carolina’s 2023 congressional, State House, and State Senate maps. They argue that the districts were drawn to dilute the voting power of Black communities, particularly in urban centers like Greensboro, Winston-Salem, and Wilmington, as well as in rural areas known as the Black Belt.

The trial in Williams concluded on July 9, 2025, featuring testimony from Black community leaders who stated that the new maps divided historically unified communities. Plaintiffs contend that these divisions amount to racial gerrymandering. The maps, however, will remain in effect for the 2024 election regardless of the court's ruling.

Defending the maps, Republican lawmakers argue they were drawn using traditional redistricting principles and partisan considerations—not racial ones. Under current legal standards, plaintiffs must “disentangle” race from partisanship to prove a map was racially discriminatory, a high evidentiary bar established in recent rulings such as Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP and earlier cases like Miller v. Johnson and Shaw v. Reno. Courts also presume that legislatures act in good faith unless proven otherwise, making direct or circumstantial evidence of racial intent essential and difficult to obtain.

Data from recent elections shows that more than 80% of Black voters in the state support Democratic candidates. This makes it challenging to determine whether the intent behind redistricting is racial or purely political, especially when partisanship and race align closely.

Additionally, critics have pointed to the racial and gender composition of the state legislature as evidence of the impact of gerrymandering. While the Democratic caucus is majority-minority and majority-female, the Republican caucus is 98% white and 87% male.

Gerrymandering affects both the state and national levels of governance. In 2024, Democrats won 51% of the statewide vote for the House but secured only 41% of the seats. In the State Senate, Republicans hold 12% more seats than their share of the vote would suggest.

Patterns of "packing" and "cracking" non-white communities—concentrating them into a few districts or splitting them across many—have long been common redistricting tactics. One example cited in litigation is the "awkward notch" carved into a Wilmington district, which allegedly moved a predominantly Black area into a district with more conservative-leaning rural counties.

Legal efforts to challenge these maps continue. Former North Carolina Supreme Court Justice Bob Orr is representing plaintiffs in a separate lawsuit challenging the fairness of legislative districts on broader constitutional grounds. He argues that the current maps undermine the constitutional right to fair elections.

“Everyone in North Carolina has a constitutional right to fair elections,” Orr said. “If the government can ‘rig’ elections, then the entire basis for representative democracy is undermined and ultimately destroyed.”

Although federal law requires congressional districts to have nearly equal populations, North Carolina allows up to a 5% deviation for State House and Senate districts. Over time, this can result in significant disparities, with some districts having tens of thousands more voters than others, potentially giving rural voters greater influence than those in urban or suburban areas.

One proposed solution is the establishment of an independent redistricting commission, similar to those adopted in other states. However, such a change would likely require legislative approval, which is challenging under a Republican near-supermajority elected in part through the current maps.

At the national level, President Donald Trump has encouraged Republican-led states like Texas to pursue aggressive redistricting strategies. In response, some Democrats, including former North Carolina Congressman Wiley Nickel, have argued that blue states should adopt similarly partisan maps to counteract Republican efforts.

“Blue states will need to match Republican gerrymandering, for the time being, in order to preserve our democracy,” Nickel wrote in a recent op-ed.

Meanwhile, some prominent North Carolina politicians who have previously criticized gerrymandering—such as Governor Josh Stein and Attorney General Jeff Jackson—have remained relatively quiet about current redistricting efforts in other states. Their silence may reflect the fact that North Carolina’s maps are unlikely to be revisited until after the next Census in 2030, barring successful legal challenges.