By: Jordan Meadows

Staff Writer

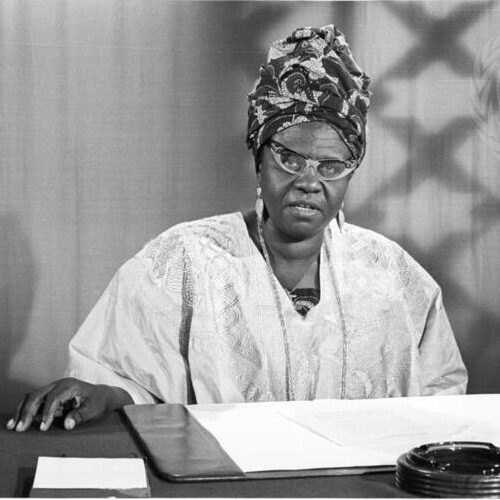

Angie Brooks was a diplomat, jurist, and global leader whose life reflected intellectual achievement and courage, particularly as a black woman in the mid-20th century navigating education, law, and international politics.

Because her parents could not afford to raise her, she was fostered to a widowed seamstress in Monrovia. By the age of eleven she had taught herself to type and earned money copying legal documents to pay for school, later working as a stenotypist for the Liberian Justice Department to finance her high school education. Married at fourteen to Counselor Richard A. Henries, who later became Speaker of the Liberian House of Representatives, she became a mother of two before eventually divorcing, all while continuing to pursue her education and professional goals.

Because her parents could not afford to raise her, she was fostered to a widowed seamstress in Monrovia. By the age of eleven she had taught herself to type and earned money copying legal documents to pay for school, later working as a stenotypist for the Liberian Justice Department to finance her high school education. Married at fourteen to Counselor Richard A. Henries, who later became Speaker of the Liberian House of Representatives, she became a mother of two before eventually divorcing, all while continuing to pursue her education and professional goals.

Brooks’s work as a typist and court stenographer sparked her interest in law, as she observed firsthand the flaws and inequities within the legal system. Determined to change those laws despite strong prejudice against women in the legal profession, she pursued legal training at a time when Liberia had no formal law schools. She successfully passed the bar exam.

Seeking further education, Brooks applied to Shaw University in Raleigh. As a divorced mother of two with limited financial resources, she could not afford the journey to the United States, but after appealing to Liberian President William V. S. Tubman, her determination impressed him enough that he arranged payment for her travel.

Brooks’s years in North Carolina were transformative and challenging: while studying at Shaw University, she worked multiple jobs as a dishwasher, laundress, library assistant, and nurse’s aide to support herself and her children. She became a member of the Eta Beta Omega chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in social science in 1949.

Yet her time in Raleigh also exposed her to the harsh realities of racial segregation in the Jim Crow South. Outraged by discriminatory laws and customs, Brooks refused to ride segregated buses and instead drove herself everywhere, asserting her dignity and autonomy in everyday life. Her experiences as an black African woman in the segregated South deeply informed her understanding of racial injustice and strengthened her resolve to advocate for equality on a global stage.

After Shaw University, Brooks continued her academic journey with distinction, earning a Bachelor of Law degree and a Master of Science in political science and international relations from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She also completed graduate work in international law at the University of London in the early 1950s, later earning a Doctor of Civil Law degree from the University of Liberia in 1964, as well as honorary Doctor of Law degrees from Shaw University and Howard University.

Returning to Liberia, she made history as the first woman to serve as Assistant Attorney-General of Liberia from 1953 to 1958 and as a counsellor-at-law to the Supreme Court. She also founded the Department of Law at the University of Liberia. Trained by the United States Foreign Service, she joined the Liberian delegation to the United Nations in 1954 and soon became Liberia’s permanent representative. Over the years, she earned a reputation for substance, integrity, and reform-minded leadership, determined to close the gap between the United Nations’ lofty commitments and meaningful action.

Her connection to Raleigh resurfaced dramatically in 1963, when Brooks returned to North Carolina as Liberia’s United Nations ambassador to deliver a speech at North Carolina State University. After the event, she and N.C. State professor Allard Lowenstein attempted to eat lunch at two downtown Raleigh restaurants, the S & W Cafeteria and the Sir Walter Coffee Shop, but were refused service because Brooks wasn’t white. One manager even suggested she could work there as a cook or waitress but would not be served as a customer. Despite her diplomatic status, Brooks faced the same racial discrimination she had known years earlier as a student. The incident, reported by the press, brought national attention to segregation in North Carolina and prompted Governor Terry Sanford to issue a formal apology on behalf of the state.

Despite these experiences in the American South, Brooks, in 1969, achieved a historic milestone by becoming the first African woman elected President of the United Nations General Assembly and only the second woman from any nation to hold that position.

Throughout her career, Brooks remained committed to advancing women’s rights and access to the legal profession. She served as vice president of the International Federation of Women Lawyers from 1956 to 1959 and continued to break barriers when she was appointed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Liberia in 1977, becoming the first woman to hold that position.

Beyond her public achievements, she lived out her values privately by fostering at least 47 Liberian children in honor of the woman who had raised her. Although she hoped to return to Liberia permanently, Angie Brooks died in Houston, Texas, in 2007. She was honored with a state funeral in Liberia and buried in her birthplace in Montserrado County, remembered as a pioneering woman whose life and values bridged continents.