By Jordan Meadows

Staff Writer

Before Brick became known as a place of learning, the land in Edgecombe County carried the weight of the Civil War and slavery. As Union armies moved south in a final effort to end the conflict, General Oliver O. Howard passed through North Carolina, while General L.G. Estes traveled an eastern route through towns such as New Bern, Kinston, and Rocky Mount. When Estes reached this area, he reportedly admired it so deeply that he vowed to return after the war and buy land there.

Though peace was declared before the armies reached Richmond, Estes kept his word. After the war, he purchased more than 1,100 acres in Edgecombe County—land that would become home to one of the most important Black educational institutions in eastern North Carolina.

Before Estes, the property had belonged to Mason Wiggins, a prominent farmer, and earlier to the Garrett brothers, whose family wealth later reached into banking and manufacturing. During slavery, the plantation was reportedly used to “break in” enslaved Africans and still bore the site of a whipping post. After the war, Estes attempted to farm cotton, corn, peaches, strawberries, and other crops, shipping goods from a private rail siding. But debt overtook him, and the land eventually fell into the hands of Mrs. Julia Elma Brewster Brick, a wealthy widow from Brooklyn, New York.

Before Estes, the property had belonged to Mason Wiggins, a prominent farmer, and earlier to the Garrett brothers, whose family wealth later reached into banking and manufacturing. During slavery, the plantation was reportedly used to “break in” enslaved Africans and still bore the site of a whipping post. After the war, Estes attempted to farm cotton, corn, peaches, strawberries, and other crops, shipping goods from a private rail siding. But debt overtook him, and the land eventually fell into the hands of Mrs. Julia Elma Brewster Brick, a wealthy widow from Brooklyn, New York.

Mrs. Brick’s ownership marked a turning point not only for the land but for Black North Carolinians. In a chance encounter at a Brooklyn church, she approached William A. Sinclair, a Fisk University graduate and financial agent for Howard University, with a bold idea: she wanted her North Carolina farm used to educate poor Black children who could not afford schooling elsewhere, giving them the chance to work their way through school.

Though Howard University did not conduct extension schools, Sinclair and General Oliver O. Howard guided her to the American Missionary Association (AMA), a leading philanthropic organization educating Black people across the South after the Civil War.

Through the AMA, Mrs. Brick donated the land—later expanding the gift and contributing thousands of dollars in cash—to establish what became the Joseph Keasbey Brick Agricultural, Industrial and Normal School. Founded in 1895, the school was named for her late husband, a civil engineer whose work on public infrastructure helped build her fortune.

The AMA sent Thomas S. Inborden, an Oberlin and Fisk-educated educator born to free parents, along with five teachers, to launch the school. When Inborden arrived, conditions were rough: unfinished buildings, mosquitoes, wild animals, and nightly disturbances underscored just how desperately the community needed stability, education, and opportunity.

Mrs. Brick believed Black students should master practical skills alongside academics, and the curriculum required every student to take industrial classes. Girls learned sewing and domestic arts; boys trained with tools, agriculture, blacksmithing, woodworking, and mechanical drawing. Students helped maintain the campus while receiving instruction in arts and sciences. This dual approach allowed the school to sustain itself, producing food from its farmland and even operating a successful mail-order honey business.

The school grew quickly. Enrollment climbed as high as 460 students, drawing children and young adults eager for opportunity. Brick also developed a strong cultural presence, particularly in music. Concerts in the late 1890s drew white audiences, and by the 1930s, the school was staging ambitious musical performances reported in national Black publications. Athletics also thrived, with men’s and women’s basketball teams, football, and membership in the North Carolina Athletic Association.

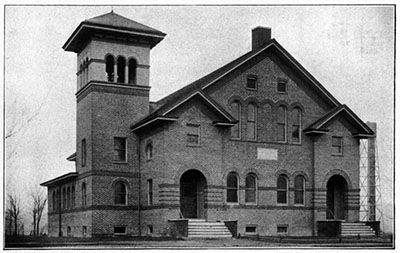

In 1925, Brick expanded its mission further by opening a junior college, offering rigorous coursework in arts, sciences, education, and even pre-medicine. At its peak, the campus included brick dormitories, classroom buildings, workshops, farm structures, and Ingraham Chapel, whose auditorium seated 1,000 people. Fifty acres served as the school campus, while additional land provided food or income through tenant farming.

Yet, like many Black institutions, Brick could not escape the economic devastation of the Great Depression. Enrollment declined, funding from the AMA was sharply reduced, and by the late 1920s and early 1930s, the school was forced to close.

After the school’s closure, the campus found new life as the Brick Rural Life School, emphasizing cooperative farming and rural improvement. Today, the land is home to the Franklinton Center at Bricks, a United Church of Christ retreat and educational facility. Under new leadership, the center continues to serve the community through gatherings, land-based innovation, and food production, while plans are underway to establish an African American museum honoring the site’s history.